April 18, 2018

Grayson Perry’s ‘All in the Best Possible Taste’ three part series

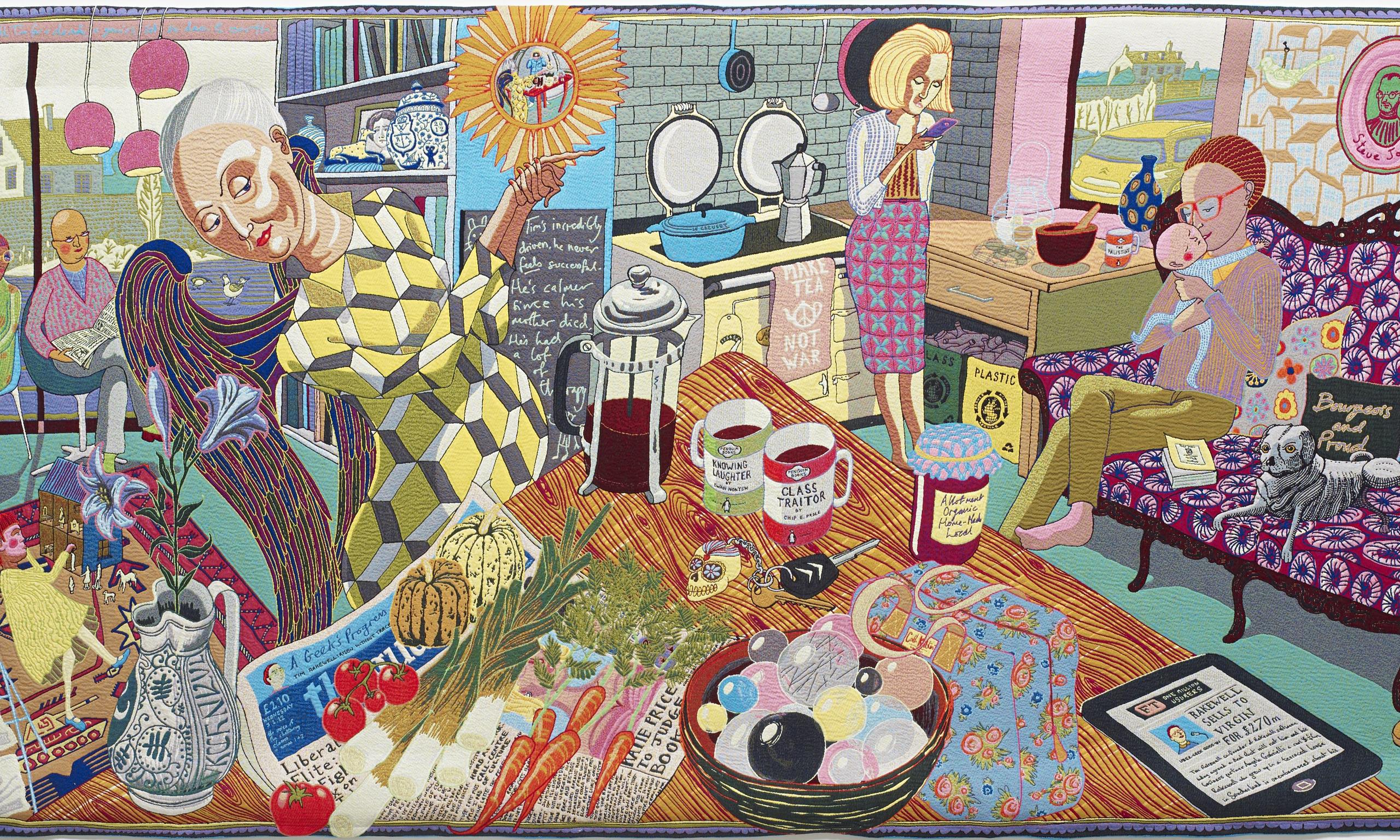

Grayson Perry’s documentary exploring British class, taste and social mobility looked at the working class, middle class and upper class in a three part documentary. From his ‘taste safari’ (Perry, 2013) Perry designed tapestries that captured these three social classes named collectively ‘The Vanity of Small Differences’.

I was struck by the flamboyancy, and extravagance, of the working class in Sunderland. I found it interesting when Perry draw a comparison between people spending large amounts of money on tattoos and people spending money on art. Taking wages into consideration, the people forking out on tattoos were the more extravagant spenders – yet they would never dream of spending hundreds of pounds on a piece of art.

The upper class, in the Cotswolds, seemed to have the opposite idea about flamboyancy. Their tastes revolved around what was consider appropriate and in keeping with tradition. What struck me about this social class was the apparent lack of money to spend – undoubtedly they had wealth in property and assists but not necessarily in wages. I found it odd how people living in such grand estates could be struggling with paying heating bills and having to budget more so than many of the people I know in working class or middle class lifestyles.

The episode I found to be the most interesting was the middle class investigation. Perry went to Tunbridge Wells in Kent and visited the ‘new middle class’ as well as the more established middle class. I found myself associating with both of these middle classes – I did not feel particularly brand-led however I do feel I am aware that what I own sends a message out to people. Perry (2012) states that the middle class is ‘the class that are most aware of the meaning and status of the things that they buy… they’re (the) most self-conscious’. I see this obsession with creating and recreating oneself alive on platforms such as Instagram. It is a place where you can to some extent curate your life. Endless photos of food, travel, selfies, accomplishments etc are shared in the hope it will communicate that you have taste (content of what is uploaded will depend on your class as Perry has investigated). I did not feel online presence was explored at all in this series which would have been an interesting comparison of selfies and travel photos.

Various reviews online have praised Perry’s role in this series in his observation, want to understand, capture and communicate these people groups (despite him not being a anthropologist). I believe Perry was performing the role of artist very truly – to mirror society in the way he understands it. His chosen medium of tapestries to display his ‘findings’ was justified by cleverly worded statements such as ‘taste is woven into our class system’ (Perry, 2013).

Despite not being an anthropologist, Perry was inspired by Kate Fox’s book ‘Watching the English’ (2004) which explore unwritten codes of English behaviour. I would like to read this and find out more on this topic as in the lecture I was left stumped when Nela asked us what we think British culture truly means. I could not think past tea, royalty, politeness and bad weather. I would like to know more about not just our history in terms of facts and figures but what has shaped our culture as a nation. At present I do not feel we have a strong sense of being proud to be British – especially not the generation I am in. It would be interesting to investigate why there has beeb a change and what is the main cause be it politics, capitalism, social media, family breakdown etc. According to Perry (2013) it is ‘those unexamined ‘natural’ and ‘normal’ choices, which often say the most about us’ – trying to uncover the reasons behind these ‘normal’ choices and views would be a curious search.

I resonated with Perry as he talked about how you are shaped from your childhood home, ‘A childhood spent marinating in the material culture of one’s class means taste is soaked right through you. Cut me and, beneath the think crust of islington, it still says ‘Essex’ all the way through’ (Perry, 2013). I think this is a very frank thing to say, especially from someone situated in the artistic world which would have been undoubtable hard to navigate being a Essex transvestite potter in a high brow environment. It is refreshing to have someone like Perry build bridges of understanding between different classes – he is using his white middle class male privilege in a positive way.

I often feel a judgement when I say to someone I am from Essex (past reactions have wavered from ‘ohhhhh’ to ‘you don’t look/sound like you are from Essex?’). It shocks me to still interact with people who believe stereotypes, and of course shows such as ‘The Only Way is Essex’ do not help and if anything have exaggerated stereotypes in recent years. The Oxford English Dictionary definition of ‘Essex girl’ is ‘A brash, materialistic young woman of a type supposedly found in Essex or surrounding areas in the south-east of England’, other definitions include unintelligent, promiscuous and ‘devoid of taste’. No other stereotype exists in the dictionary that defines someone from a particular place. No wonder people are shocked when they come across an ‘Essex girl’ who is polite and not overly interested in brands. The negative meaning originated in the 1980s and 90s around the time that there was a rise in social mobility.

“You can’t hear the word Essex without having a cognitive flash of all the stereotypes. It’s part of the battle, all those years of history behind the word.” – Sadie Hasler, Southend-on-Sea (BBC News)

There was a petition to remove, change and ‘reclaim’ this definition (which I signed and shared). As much as someone may judge me for where I am from, I find it extremely ignorant of someone to comment about my accent or ridicule my taste which they assume I have. I feel this stigma negatively affects girls and women that I know and is being left behind in feminist discussions. Having a definition in the dictionary enforces, instead of challenging, this stereotype and does nothing to empower the women who have grown up and live in this county.

Overall, the social classes all seemed to have a strong sense of community and their taste decisions are made to ‘demonstrate loyalty’, show that they belong or to respect their heritage (Perry, 2013). Two methods of social mobility seem to arise through education and increased wealth. Stephen Bayley, a cultural critic, summed up that good taste is that which does not alienate your peers.

References:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/24/end-of-the-essex-girl-3000-people-sign-petition-calling-on-dicti/

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-37761668

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/Essex_girl

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/7368909/What-is-an-Essex-Girl.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-essex-39125171

http://www.radiotimes.com/news/2012-06-12/grayson-perry-taste-is-as-important-as-ever/

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-features/10117264/Grayson-Perry-Taste-is-woven-into-our-class-system.html

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2012/jun/19/best-possible-taste-grayson-perry

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2012/jun/12/tv-review-grayson-perry

http://www.channel4.com/info/press/programme-information/all-in-the-best-possible-taste-with-grayson-perry

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/9341781/All-in-the-Best-Possible-Taste-with-Grayson-Perry-Channel-4-review.html

I was struck by the flamboyancy, and extravagance, of the working class in Sunderland. I found it interesting when Perry draw a comparison between people spending large amounts of money on tattoos and people spending money on art. Taking wages into consideration, the people forking out on tattoos were the more extravagant spenders – yet they would never dream of spending hundreds of pounds on a piece of art.

The upper class, in the Cotswolds, seemed to have the opposite idea about flamboyancy. Their tastes revolved around what was consider appropriate and in keeping with tradition. What struck me about this social class was the apparent lack of money to spend – undoubtedly they had wealth in property and assists but not necessarily in wages. I found it odd how people living in such grand estates could be struggling with paying heating bills and having to budget more so than many of the people I know in working class or middle class lifestyles.

The episode I found to be the most interesting was the middle class investigation. Perry went to Tunbridge Wells in Kent and visited the ‘new middle class’ as well as the more established middle class. I found myself associating with both of these middle classes – I did not feel particularly brand-led however I do feel I am aware that what I own sends a message out to people. Perry (2012) states that the middle class is ‘the class that are most aware of the meaning and status of the things that they buy… they’re (the) most self-conscious’. I see this obsession with creating and recreating oneself alive on platforms such as Instagram. It is a place where you can to some extent curate your life. Endless photos of food, travel, selfies, accomplishments etc are shared in the hope it will communicate that you have taste (content of what is uploaded will depend on your class as Perry has investigated). I did not feel online presence was explored at all in this series which would have been an interesting comparison of selfies and travel photos.

Various reviews online have praised Perry’s role in this series in his observation, want to understand, capture and communicate these people groups (despite him not being a anthropologist). I believe Perry was performing the role of artist very truly – to mirror society in the way he understands it. His chosen medium of tapestries to display his ‘findings’ was justified by cleverly worded statements such as ‘taste is woven into our class system’ (Perry, 2013).

Despite not being an anthropologist, Perry was inspired by Kate Fox’s book ‘Watching the English’ (2004) which explore unwritten codes of English behaviour. I would like to read this and find out more on this topic as in the lecture I was left stumped when Nela asked us what we think British culture truly means. I could not think past tea, royalty, politeness and bad weather. I would like to know more about not just our history in terms of facts and figures but what has shaped our culture as a nation. At present I do not feel we have a strong sense of being proud to be British – especially not the generation I am in. It would be interesting to investigate why there has beeb a change and what is the main cause be it politics, capitalism, social media, family breakdown etc. According to Perry (2013) it is ‘those unexamined ‘natural’ and ‘normal’ choices, which often say the most about us’ – trying to uncover the reasons behind these ‘normal’ choices and views would be a curious search.

I resonated with Perry as he talked about how you are shaped from your childhood home, ‘A childhood spent marinating in the material culture of one’s class means taste is soaked right through you. Cut me and, beneath the think crust of islington, it still says ‘Essex’ all the way through’ (Perry, 2013). I think this is a very frank thing to say, especially from someone situated in the artistic world which would have been undoubtable hard to navigate being a Essex transvestite potter in a high brow environment. It is refreshing to have someone like Perry build bridges of understanding between different classes – he is using his white middle class male privilege in a positive way.

I often feel a judgement when I say to someone I am from Essex (past reactions have wavered from ‘ohhhhh’ to ‘you don’t look/sound like you are from Essex?’). It shocks me to still interact with people who believe stereotypes, and of course shows such as ‘The Only Way is Essex’ do not help and if anything have exaggerated stereotypes in recent years. The Oxford English Dictionary definition of ‘Essex girl’ is ‘A brash, materialistic young woman of a type supposedly found in Essex or surrounding areas in the south-east of England’, other definitions include unintelligent, promiscuous and ‘devoid of taste’. No other stereotype exists in the dictionary that defines someone from a particular place. No wonder people are shocked when they come across an ‘Essex girl’ who is polite and not overly interested in brands. The negative meaning originated in the 1980s and 90s around the time that there was a rise in social mobility.

“You can’t hear the word Essex without having a cognitive flash of all the stereotypes. It’s part of the battle, all those years of history behind the word.” – Sadie Hasler, Southend-on-Sea (BBC News)

There was a petition to remove, change and ‘reclaim’ this definition (which I signed and shared). As much as someone may judge me for where I am from, I find it extremely ignorant of someone to comment about my accent or ridicule my taste which they assume I have. I feel this stigma negatively affects girls and women that I know and is being left behind in feminist discussions. Having a definition in the dictionary enforces, instead of challenging, this stereotype and does nothing to empower the women who have grown up and live in this county.

Overall, the social classes all seemed to have a strong sense of community and their taste decisions are made to ‘demonstrate loyalty’, show that they belong or to respect their heritage (Perry, 2013). Two methods of social mobility seem to arise through education and increased wealth. Stephen Bayley, a cultural critic, summed up that good taste is that which does not alienate your peers.

References:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/24/end-of-the-essex-girl-3000-people-sign-petition-calling-on-dicti/

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-37761668

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/Essex_girl

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/7368909/What-is-an-Essex-Girl.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-essex-39125171

http://www.radiotimes.com/news/2012-06-12/grayson-perry-taste-is-as-important-as-ever/

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-features/10117264/Grayson-Perry-Taste-is-woven-into-our-class-system.html

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2012/jun/19/best-possible-taste-grayson-perry

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2012/jun/12/tv-review-grayson-perry

http://www.channel4.com/info/press/programme-information/all-in-the-best-possible-taste-with-grayson-perry

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/9341781/All-in-the-Best-Possible-Taste-with-Grayson-Perry-Channel-4-review.html